KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — The cheers of fans and whacks from bats sending baseballs soaring through the skies of downtown may be a transformational vision for Knoxville, but critics of a new stadium proposal say that dream should not hinge on investments from taxpayers.

"It's an absolute boondoggle in every sense of the word," said one critic of the proposal to use $65 million in sales tax-backed bonds to build a new stadium for baseball, concerts, and other events on an old industrial site in East Knoxville.

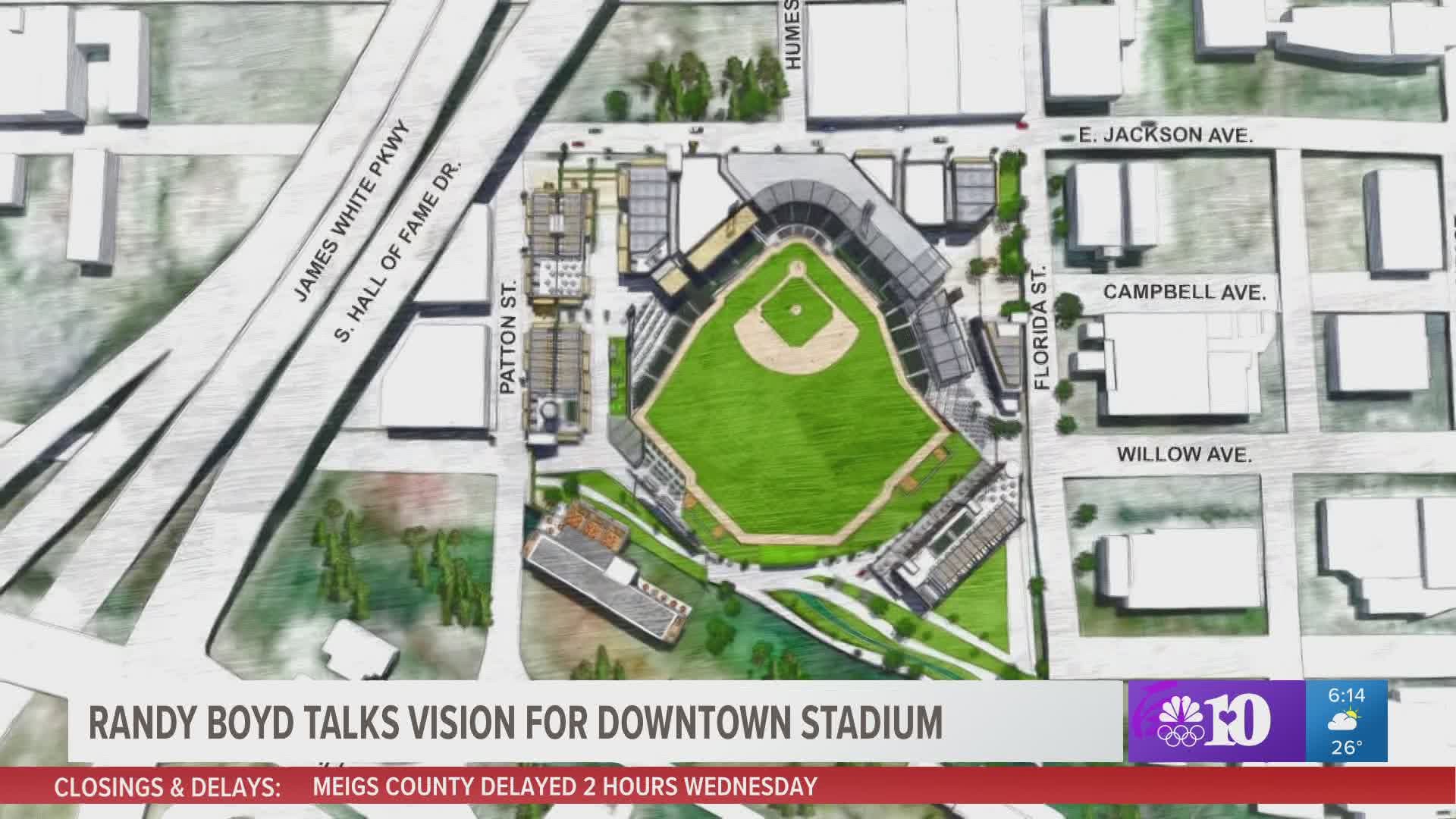

The plan to build the stadium is the vision of Tennessee Smokies owner Randy Boyd, a millionaire entrepreneur and the University of Tennessee System president. He foresees a community gathering place -- a kind of "People's Park" -- for everyone from baseball fans to fans of farmers markets and community concerts.

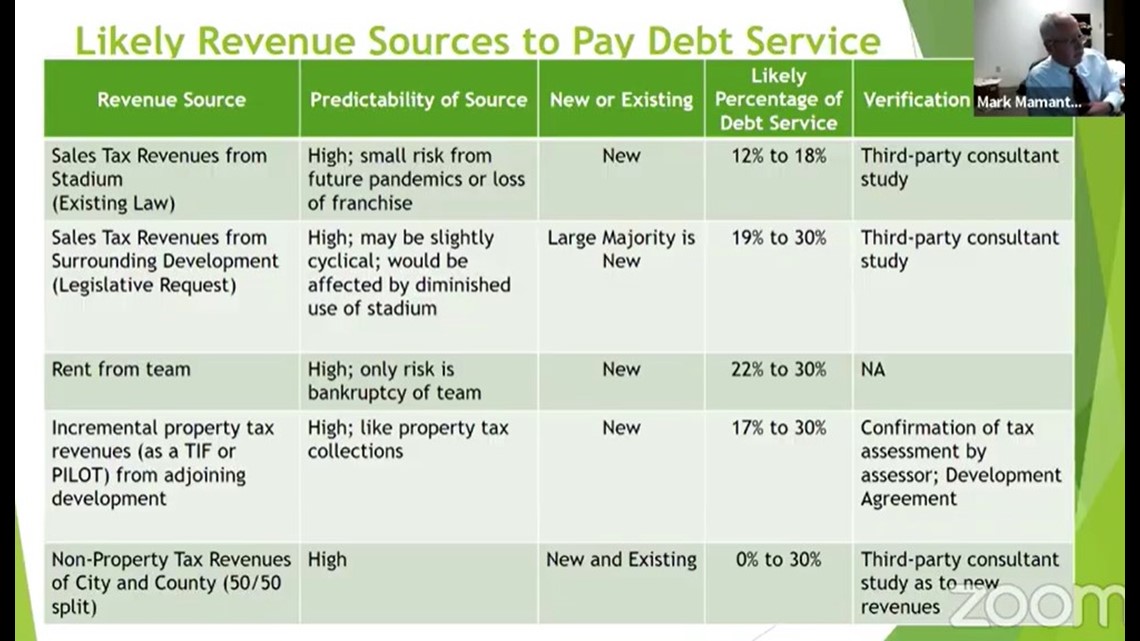

To help fund the stadium, legislation was introduced this month in the Tennessee General Assembly that would allow local governments to use state and local sales taxes. The money would be collected from a defined area around the proposed stadium and include the sales at restaurants and retail stores scattered throughout the Old City.

Sales taxes collected from sales inside the stadium itself also would be used. The team also would pay rent.

"Is money better spent on education, community safety and other infrastructure needs that are a higher priority?" said Erik Wiatr, a realtor and political activist questioning the use of any taxpayer money to help build the stadium.

Private investors are ready to spend more than $140 million on apartments, shops and restaurants surrounding the ballpark. The stadium itself would be built through a sports authority that could issue roughly $65 million in bonds to be paid back over perhaps 30 years.

"If it were to happen, it would be one of the biggest developments in our city since the World's Fair Park," explained Vice Mayor Gwen McKenzie who represents the City Council District where the stadium is supposed to be built.

It's possible local government will have to spend another $15 million to $20 million to upgrade infrastructure around the site.

Knoxville native and former University of Tennessee football player Steve Davis is an investor in the stadium project and leads a successful development company in Chicago.

"My mom lived in Austin Homes," said Davis, "I used to play baseball in Cal Johnson Park."

Growing up in Knoxville, Davis was one of the first Black students to attend a newly desegregated Bearden Elementary School. In an interview from his office in Chicago, he said overall the new stadium project would help stimulate the Knoxville economy and pump millions of dollars into an area with higher unemployment than almost any other part of the city.

"Equally as important, it reconnects East Knoxville to downtown. It's an economic shot in the arm. While most people look at gentrification as regressive, I think what we're doing is an investment that is progressive," said Davis.

However, there are other critics concerned about whether the area will see a return on a big investment by taxpayers.

"Where is the money ultimately going to go?" said Charles Al-Bawi, an activist and skeptic of the stadium. "Is it the people in the community that's going to benefit from it? Or is it going to be a handful of developers?"

A petition opposing taxpayer funding for a new baseball stadium has collected almost 600 signatures. Wiatr also started a Facebook page and campaign against the stadium — Knoxville Against Taxpayer Stadiums.

In it, activists warn that the costs of the COVID-19 pandemic and other community projects is already squeezing Knoxville's budget. Those same critics argue using taxpayer funds to back building a baseball stadium is money elected leaders should avoid putting at risk.

"Randy Boyd is probably the best businessman, if not one of the best business people that we have in the county. You know, if he cannot figure out how to make a stadium profitable for him, the administrators of the city of Knoxville and Knox County aren't going to figure it out, right?" said Wiatr.

City and county staff say funding would be spread across enough sources, including team rent, that government finances aren't threatened.

Al-Bawi also said he wants to make sure community members benefit from the stadium first and that leaders account for unintended consequences.

"We want to see that people who have lived in this community for a long time benefit from that development and not be pushed out in the form of increased property taxes and the like," he said.

City and county staff say no property taxes can be used in the project.

Some have raised questions about parking availability in the area when the stadium is built.

Supporters including Boyd's staff say in an urban setting such as the targeted site there's not generally dedicated surface parking nearby. The idea is for people to walk, bike, use public transportation or park in nearby garages.

A parking study commissioned by Boyd's groups shows there are 1,333 existing parking spaces within a quarter-mile radius of the stadium; 7,675 within a half-mile radius; and 15,730 within a mile radius, developers say.

To get a guarantee that the Knoxville community will benefit from the baseball stadium, Al-Bawi said he wants to see more public debate. He wrote a letter with other community groups to developers and elected leaders to jumpstart a conversation, and as he said, "get a seat at the table" when it comes to making the final call.

Another critic, Mark Cunningham, said that publicly financed stadiums tend to fail more often than succeed in the long term. He said communities tend to lose money by publicly funding stadiums similar to the proposed Knoxville project.

Cunningham advocates across the state for limited government through his work with the "The Beacon Center," a Nashville-based, non-partisan non-profit organization.

"It's tax dollars going to millionaire owners that don't need it to build a stadium," he said.

Demolition crews are already tearing down old buildings on the old Lays meatpacking plant site at Jackson Avenue. A tentative working timeline estimates construction could start in the fall and finish in 2023.

Before then, though, some say the developers need to gather more support from the community before beginning work on the project.

"They want fans to be at the game," Al-Bawi said. "You have to have them as a part of the process and get them to feel like they're on the team."

Neighborhood association leaders representing areas that ring the outskirts of the old industrial site include: Parkridge, Fourth and Gill and Austin Homes. In response to emailed questions from 10News, leaders from those three areas report a mix of responses about the project from their neighbors. Of particular concern are questions about a surge in traffic and noise tied to a new downtown stadium.

Leaders on both the Knoxville City Council and Knox County Commission are planning for more public discussion and public input on the stadium project that will need majority votes in both elected bodies by this summer for the plan to stay on a two-year construction timeline.