In the 1970s , '80s and '90s, testimony that's now regarded as "junk science" helped send some Tennesseans to prison.

Today, a small group of University of Tennessee law students is patiently working to give those inmates a chance at freedom.

Under the guidance of adjunct professor and Knoxville defense attorney Steve Johnson, the College of Law students have for the past year or so been poring through old evidence and searching for lost evidence tied to human hair that convicted people accused of violent crimes, including rape and murder.

They're getting real-life experience about the American justice system while also learning how to be a lawyer.

It's daunting, frustrating and uplifting work.

"There is a lot of chaos in trying to find where the old evidence is, and that can end up being sometimes a monumental effort that can take months or take longer than months. It can sometimes take years," Johnson told 10News.

One group has just finished their time on the project and handed it off to another. They say it's been an enriching and challenging experience.

"It's an emotional rollercoaster for us because we invest a lot of time into it, and we get our hopes up thinking that we’ve found this crucial piece of evidence that we’ve been looking for," said law student Christy Smith. "And then, a lot of times, it just falls through."

'MISCARRIAGE OF JUSTICE'

In April 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice and the FBI made an extraordinary announcement: Forensic hair fiber evidence once used in criminal courtrooms around the nation was essentially bogus. It was unreliable and had almost certainly convicted people who could very well have been innocent, the DOJ acknowledged.

The department came to that conclusion after it went back and looked at a sample of cases in which FBI hair experts had testified. Modern-day DNA analysis revealed the microscopic hair testimony to be essentially worthless.

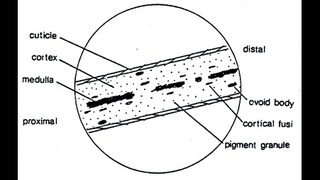

Several decades ago, before the arrival of DNA testing, FBI technicians in a lab would take hair fiber associated with a victim, study it under a microscope and try to match it with a sample from a suspect. Typically the hair fiber had been recovered at crime scenes or found on crime victims.

If examiners got any kind of match, all they typically could say was there was a degree of probability that the samples matched. Prosecutors used such testimony to hep convict defendants in murder cases, rapes and other violent crimes.

But it turned out FBI personnel, backed by the authority of a powerful federal agency, had given bad testimony in at least 90 percent of the criminal trials studied in a nationwide review.

Twenty-six of of 28 FBI agent/analysts had made either incorrect statements at trial or submitted flawed lab statements as part of their work, the government acknowledged last year.

The advancement of DNA analysis exposed their failures.

Genetic testing of evidence was scientific and sound. A simple microscopic review was unreliable and unscientific.

"In some cases (the evidence) turned out to be not organic material at all," Johnson said. "In some cases, it turned out to be hair from an animal – not even human hair. And in a lot of cases it turned out to be human hair but human hair not from the defendant."

The department and the FBI, in a rare union with adversaries, then began cooperating with the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and a legal advocacy group called the Innocence Project, which has used DNA the past 15 years or so to help exonerate innocent defendants.

Peter Neufeld, co-founder in the early 1990s of the national Innocence Project, last year called the government's handling of the hair analysis an "epic miscarriage of justice." Underscoring the seriousness of the matter, the DOJ carried Neufeld's slam in its own press release recognizing mass errors in microscopic hair analysis.

Now the four entities are united in tackling the problem of tainted evidence derived from bad science.

"It’s really historic that they’ve gone in and done this," Johnson said. "And it’s resulted from advances in DNA technology and being able to determine in an exact way whether or not this evidence is reliable."

LOCAL REVIEWS

As a result of the review, states, law enforcement agencies and local prosecutors were directed to begin looking at whether they had any cases tainted by microscopic hair fiber testimony.

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation had through the years sent a number of cases involving "presumed human hair samples" to the FBI for examination, said spokesman Josh DeVine. The TBI did none of that work itself.

Several years ago, as a result of the hair fiber review, the FBI began asking the TBI about those cases. The TBI in turn identified prosecutors in Tennessee who oversaw such cases.

"We have since communicated with the local law enforcement agencies involved in cases that required FBI analysis of hair and encouraged them to communicate directly with the FBI about the case disposition and any issues that may have since resulted," DeVine said in an email to 10News.

The Knox County District Attorney General's Office got about 10 inquiries from the DOJ and the FBI, according to prosecutor Kyle Hixson.

The DA's office found no instance in which its use of the evidence had a "material effect" on a case, Hixson said.

"What we found in a lot of them was we didn't even use the hair fiber analysis," he told 10News. "It may have been conducted but was not used."

Still, the prosecution has forwarded what it knows to the defendants' last known attorneys, Hixson said.

The feds, NACDL and Innocence Project participants continue to cooperate.

When the government becomes aware of old cases that involved microscopic hair fiber analysis, it forwards them to Innocence Project participants across the country.

Johnson, along with lawyer Kenneth Irvine, founded the Tennessee Innocence Project chapter more than 15 years ago.

Johnson is a UT College of Law graduate who now teaches at the school while also practicing law with the Ritchie, Dillard, Davies, and Johnson law firm in downtown Knoxville.

SCAVENGER HUNT

So far about 20 Tennessee cases have been identified in which microscopic hair fiber testimony by the FBI played a part in an inmate's conviction, according to Johnson.

The attorney said he could not discuss specifics about the cases or inmates.

It has fallen to his students to work the cases and track down the old hair evidence. It'll likely take many more months, if not years, to see real progress.

Like the lawyers they will some day be, the law students view the inmates as their clients.

They've discovered a troubling fact across the state: There's no standard way to keep evidence from old criminal cases.

Some counties leave it up to the clerk's office to store the evidence. Some DAs keep it; some law enforcement agencies keep it.

Johnson compares it to a scavenger hunt: Who has the evidence?

"Each local jurisdiction has a slightly different way of preserving evidence – and oftentimes not preserving evidence," law student Marshall Jensen told 10News. "A lot of it is going from the county clerk’s office to the sheriffs’ office to the police department trying to figure out what happened to evidence.

"And oftentimes evidence has been lost . It's been moved to various county offices over the course of years and you’ll pick up a hint at one office and follow that out until you find a conclusion and hopefully at the end of it find the evidence that you’re looking for. But a lot of it is chasing down leads and dead ends."

Christy Smith said the students ended up - willingly - investing "a lot of emotional energy and sleepless nights" on their clients' cases.

It's hard not to be hopeful about a specific case, said law student Tyler Caviness. But because so much time has passed since the inmate's trial, the students also have to be realistic about the chances of finding old evidence, he said.

The students are very aware that the success of the effort - an inmate's chance at freedom and exoneration - rests with them, Johnson said.

"It’s a tremendous burden but it’s a burden that we gladly accept," he said. "Part of being a lawyer is having a commitment to public service and having a commitment to our system of justice."

Law student Ronald Coleman said the students view it as an honor and a privilege to be involved in the project.

"We’re passionate about it and we’re willing to put in that time and effort to represent these people and to hunt down any potential leads," he said. "And even if we get disappointed , we know that there is a light. There’s going to be something - and I think that’s what motivates us in spite of all that."