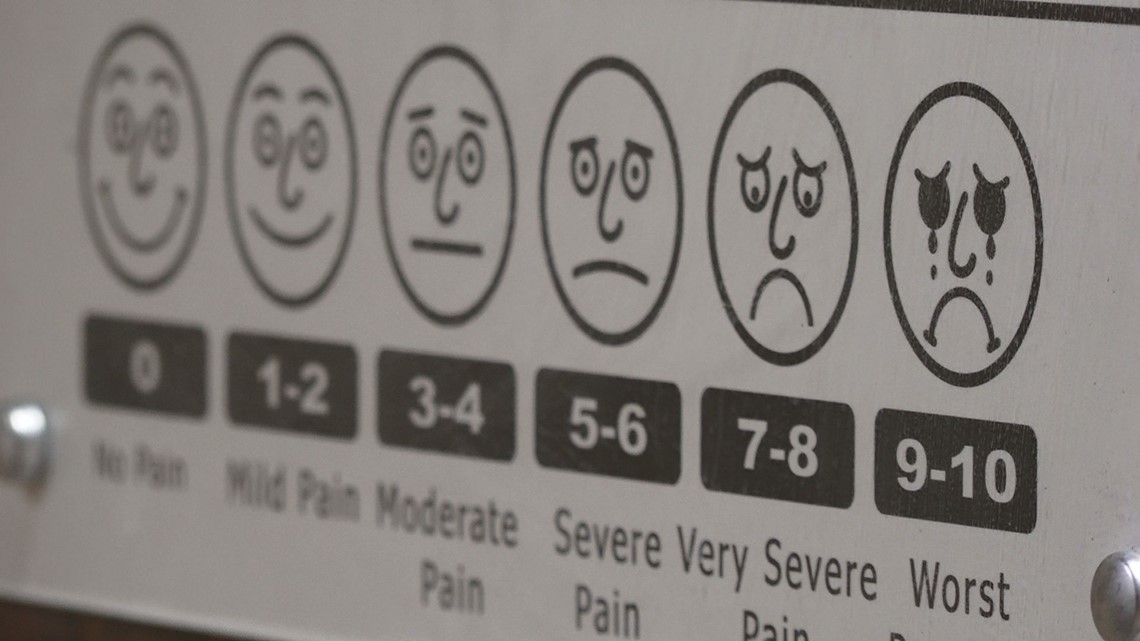

Knoxville — In the late 1990s a revolution in pain management helped lay the foundation for today's opioid epidemic.

A number of events in 2001 created tangible cornerstones in the changes.

The Joint Commission, which accredits healthcare organizations, listed pain as a vital sign. How a patient perceives their pain was used alongside pulse rate, respiratory rate, body temperature and blood pressure as indicators of a patient's condition.

The same year the Tennessee legislature passed the Intractable Pain Act. It was intended to ensure people with chronic pain could access treatment, but it opened the door to unintended consequences.

Also in 2001, a high profile lawsuit ended in a California physician paying $1.5 million dollars for not giving a patient enough pain treatment.

Though most people were not aware of the danger improper opioid use could bring, the bodies of overdose victims were already coming into the the medical examiner's office when Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Darinka Mileusnic-Polchan started working in Knoxville in 2002.

"Working with the previous medical examiner, pretty much the first week when I arrived here her warning to me was 'beware of our crisis. We have a huge crisis.' And that was 2002," Mileusnic-Polchan said. "It was obvious that we were dealing with a tremendous problem here and I was just stunned that there really was not much conversation."

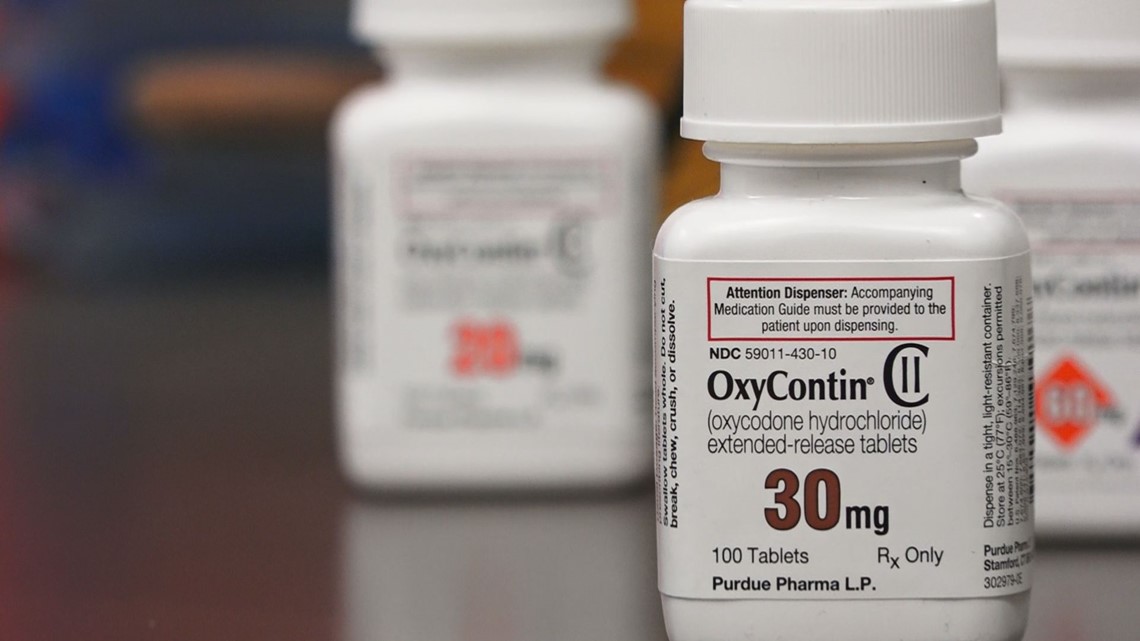

In the early 2000s OxyContin and Xanax were the most common causes of overdoses in Knox County.

The same year Mileusnic-Polchan began working in Knoxville, state lawmakers in Nashville passed the Controlled Substances Monitoring act. It created a database that collected information on drugs prescribed to patients to ensure physicians had a more comprehensive understanding the patient's existing prescriptions and to deter patients from 'doctor shopping,' or going to multiple doctor's to receive the same prescription.

The Controlled Substances Monitoring Database began collecting data in 2006.

Although the new law did help curb prescription opioid abuse, another drug garnered the most attention from law enforcement and other government leaders.

In 2005, then Gov. Phil Bredesen taughted 'Meth Free Tennessee.' As part of the act, cold medicines containing the decongestant Pseudoephedrine were moved behind the counter at pharmacies.

The campaign led to a decrease in meth labs from 2004 through 2007, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office. However, meth use has been increasing since 2007 with much of the stimulant trafficked from Mexico. The TBI now says it is at an all time high in Tennessee and it is contributing to overdoses in the state.

"When we had methamphetamine clandestine labs here, fighting obviously for good reason, we had addicted individuals who were not necessarily dying and coming to our office," Mileusnic-Polchan said. "Now, they're dying and coming to our office."

Mileusnic-Polchan says that meth now kills more people than OxyContin and Xanax. Fentanyl and fentanyl analogues are the only substances more commonly found in overdose victims.

While state efforts to mitigate the drug crisis focused on meth, pain management clinics popped up across the state. At one point pain clinics numbered more than 300 across Tennessee. Requirements as to who could own a pain clinic were relatively lax.

"I'm not so much for regulation and you certainly cannot regulate and legislate medicine, but this was on are that a lot of nefarious things were happening and regulation had to take place," Mileusnic-Polchan said.

Throughout the mid 2000s, most legislative action pertaining to prescription drugs focused on making the CSMD a more useful tool for physicians.

In the past three years lawmakers have increased the pace trying to keep up with the drug epidemic.

In 2015 the Tennessee legislature passed both the Opioid Abuse Reduction Act and the Addition Treatment Act. It also repealed and Intractable Pain Act and create more strict requirements for who could own a pain clinic.

In 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services removed pain management questions it's patient satisfaction survey.

However, steps to minimize new addictions created shifts behavior for those already abusing substances.

"Obviously the legislation worked as far as regulating the pain clinics and unscrupulous prescribing, but we have a population now of drug addicts that are looking for other sources of drugs," Mileusnic-Polchan said. "The problem is that we created this addicted population that is resorting to something else because we haven't created a program to help them otherwise. The problem with opioids in general is that it's a lifelong battle and illness. Once addiction takes root, it takes over an individual and its hard to get rid of."

The introduction of fentanyl and fentanyl-laced products in street drugs has created an even greater uptick in overdose deaths.

"IV drug abuse has skyrocketed," Mileusnic-Polchan said. "I've never seen anything like this in my life. i haven't seen it in a metropolitan city where I worked for years, where you would expect intravenous drug abuse to be just a common theme and everyday occurrence. It's actually more here."

In January, Gov. Bill Haslam announced TN Together, a $30 million dollar plan to treat the opioid epidemic from the angles of prevention, treatment and law enforcement.

Last month he signed a key provision of that plan into law that limits the amount of opioid new patients can be prescribed.

Dr. Mileusnic-Polchan thinks that plan can help prevent new addictions from taking root, but believes that it takes a more comprehensive approach to reduce the number of overdose victims entering her office.

From 2016 to 2017, overdose deaths increased by 30 percent nationwide. In Knox County in that same period, overdose deaths increased more than 40 percent. Last year 294 people died of a suspected overdose in Knox County and 2018 is on track to be even deadlier.

"That is an absolute failure of our system, what we are doing and what we are trying to accomplish," Mileusnic-Polchan said. "And not to point fingers or blame anybody, obviously we cannot be repeating the same thing and hoping for a different outcome because obviously something has to change in our attitudes."