KNOXVILLE, Tenn. — Federal courts in East Tennessee have seen a sharp increase in the need for Spanish interpreters, the result of more illegal immigration charges being sought by federal prosecutors, authorities say.

In 2015, the Eastern District of Tennessee marked 30 criminal cases that required an interpreter because the defendant, typically Hispanic, couldn't speak English, according to the Clerk's Office.

In 2016, the rate fell to 23 and then rose to 39 in 2017.

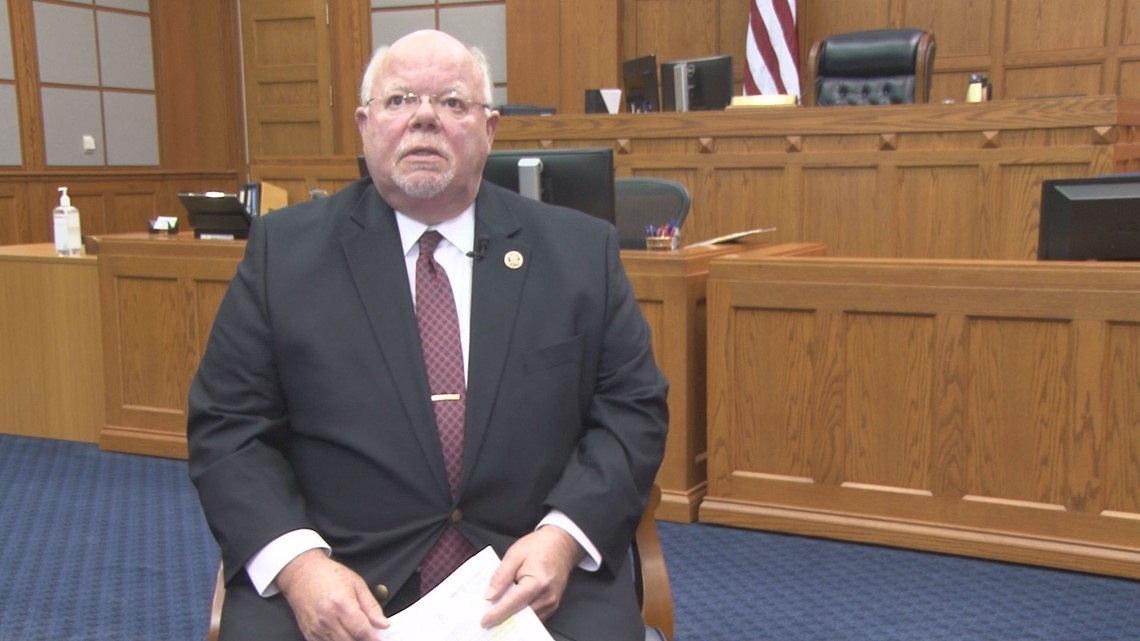

Last year, said John Medearis, clerk of the District Court, there were 102 cases in which an interpreter had to be used.

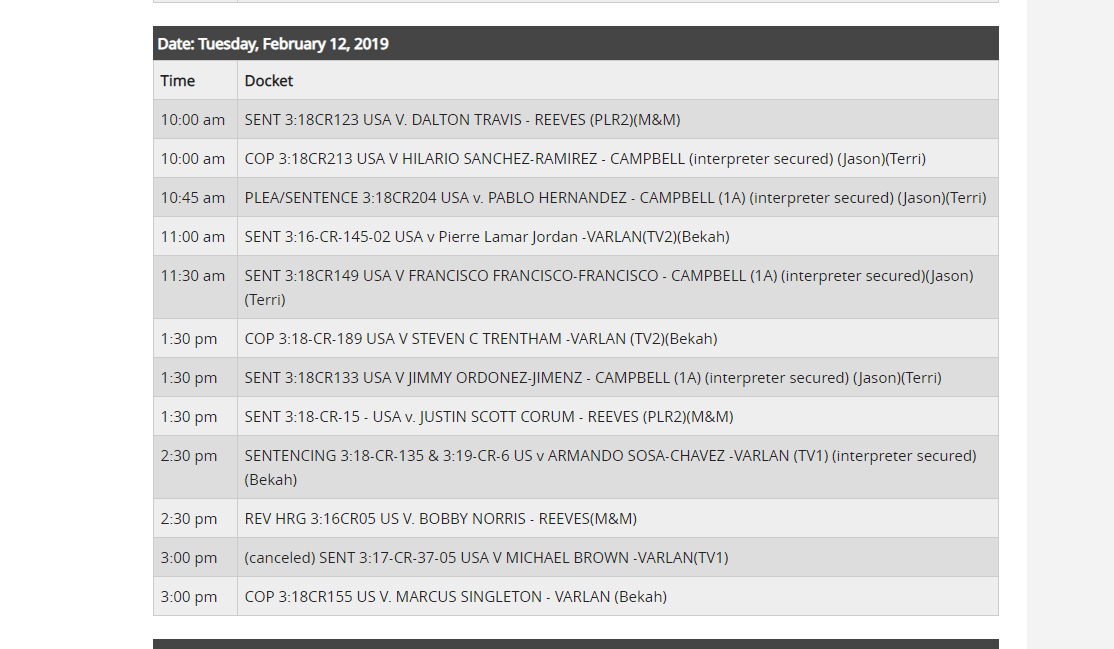

On the day 10News met with him earlier this month, interpreters were booked to handle at least five cases.

"Our need for interpreters has increased rather dramatically, particularly over the last year," he told 10News.

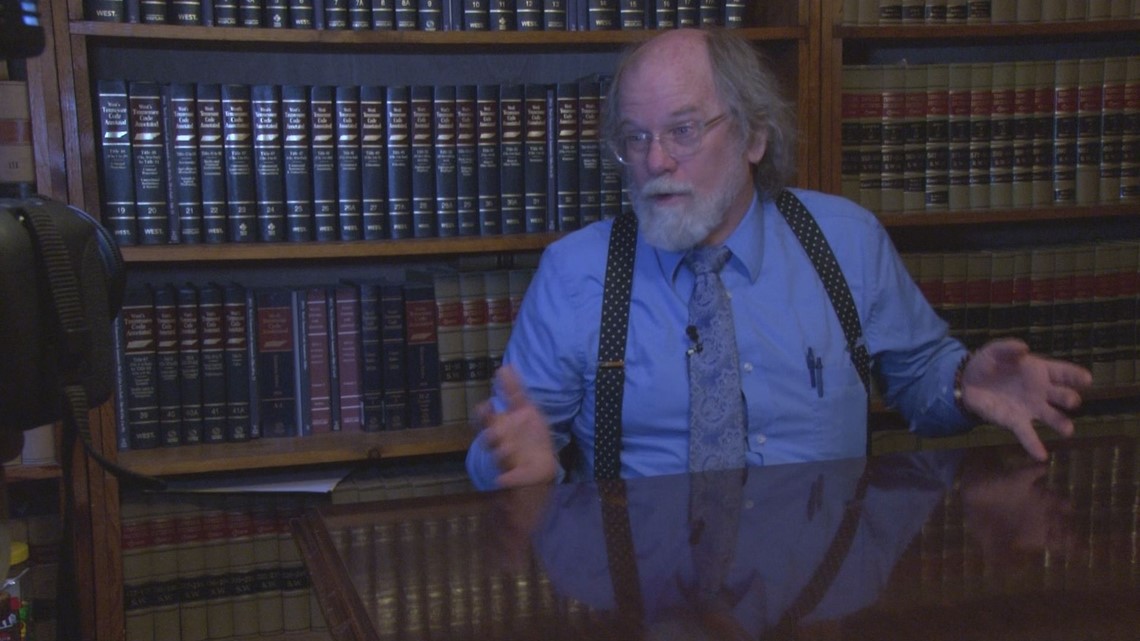

Federal prosecutors today are seeking more illegal entry charges, for example, driving the need for interpreters who can explain the case to the defendant, according to Medearis and Mike Whalen, a defense attorney for more than 20 years in the Knoxville area.

And, Whalen said, prosecutors in turn are getting their marching orders from the Department of Justice under President Trump, in office since January 2017.

To Whalen, the government is pursuing unnecessary prosecutions that typically result in a six-month punishment.

A vocal segment of the U.S. population opposes the presence of illegal immigrants, underscored by President Trump's pursuit of a wall along the Southern U.S. border and its ensuing debate.

On Tuesday, the White House reiterated its frequent refrain that a growing illegal immigration "emergency" exists on the southern border.

A spokesman for the U.S. Attorney's Office in Knoxville couldn't be reached.

Interpreting by telephone

To accommodate the demand for more interpreters, Medearis and his staff have had to become adept schedulers. They don't have their own interpreter on the payroll.

Not just anyone who speaks a foreign language can serve as a federal interpreter. Anyone who interprets on behalf of the government faces rigorous certification, Medearis said.

For some court dates, such as initial appearances, the clerk can tap a federal network of interpreters available remotely by telephone. The defendant communicates with the interpreter in the courtroom via a communication system.

So, for example, it's possible someone based in New York who works for the federal court system could be called upon to step in by phone to help interpret for a defendant in Knoxville or Greeneville. That same New Yorker also might spend part of their work day on the phone explaining legal procedures to a defendant in South Carolina or Kentucky.

West Coast interpreters could just as well be called on to phone in their help to the Eastern District of Tennessee, which stretches from Winchester, Tenn., to Chattanooga on up to Johnson, Washington and Sullivan counties.

Taxpayers -- through the federal government -- pay for the telephonic service, called the Telephone Interpreting Program.

TIP can save the district clerk's office money for routine hearings. But if a non English speaking defendant pleads guilty or goes to trial, a live interpreter must be present. A professionally qualified interpreter gets more than $400 a day to be in court.

The closest certified interpreter is in Middle Tennessee, Medearis said. So if the court needs someone in person, they either try to schedule that interpreter to come over from Middle Tennessee or they reach outside Tennessee to bring in someone, covering their travel expenses as well as their pay. For example, someone from South Carolina has been brought in to help in cases in Knoxville.

Trying to balance the needs for interpreters with a court's busy docket can be a challenge, said Mallory Garringer, deputy for U.S. Magistrate Judge Bruce Guyton.

TIP interpreters are scheduled tightly, often in 30-minute increments, so if the court's docket runs long, it's possible Garringer or one of her colleagues in a similar court will have to quickly see if the interpreter waiting to be of service is still available.

"It can be very challenging," Medearis said.

It's not unusual for the process of pleading out a case to take many months in federal court. In the meantime, the defendant is often being held in jail as an inmate at taxpayer expense.

Because illegal entry cases typically include maybe a six-month term, there's added pressure to speed up the process, which can be taxing on the federal court machinery. Otherwise the defendant can be held longer in jail than the offense for which he's been charged.

"Go away" doesn't work

Whalen said the change in prosecution is obvious.

In years past, if a federal criminal case included a non-English speaking defendant, immigration authorities would put a hold on the person that wouldn't take effect until after he'd served his time. Meanwhile, the defendant would face prosecution for the controlling crime.

Most federal offenses carry significant time -- a matter of years.

Now, more people are being rounded up and charged simply because of their immigration status, Whalen said.

The head of the Federal Public Defender's Office, which represents indigent defendants, could not be reached.

Anyone charged in this country is constitutionally guaranteed a fair trial, which means special measures may have to be taken for someone who doesn't speak English, Whalen said.

Such an aggressive pursuit of illegal residents costs money -- housing the inmate, for example, as well as employing interpreters -- and ties up an already busy court system, he said.

"It doesn't make sense economically," he said. "It doesn't make sense in any way."

He recently had such a client, a man born in Mexico with several children who have been born in the United States. That man might be deported, but the odds are he'll just come back. He's not likely to leave his family here unattended, Whalen said.

The federal immigration system faces a backlog of cases across much of the United States. Whalen, who previously has lived and worked in Mexico, said millions of people are working in the United States illegally.

But that's not going to change just because people are now being rounded up and charged for being in the country illegally, Whalen said. The nation's immigration problem is much more complicated than that, he said.

" 'Go away' is not an answer," he said. "It doesn't work. It hasn't worked. It will never work."