BLOUNT COUNTY, Tenn. — Black History Month is a time for people to honor and focus attention on African Americans who made contributions and sacrifices that helped shape the nation.

East Tennessee has many stories of how African Americans made improvements within its region.

Here's a look at some historically Black stories from within Blount County.

Maryville College's Inclusive History

Maryville College first opened as a seminary in 1819.

“Our founder, Isaac Anderson, was staunchly anti-slavery," Maryville College Archivist Amy Lundell said. "He believed that education was open to anybody. So, we had students from all ethnic backgrounds, we had, obviously a lot of white students, but we had Cherokee students, and we had former slaves. Just a wide variety of students prior to the Civil War.”

Unfortunately, the names of those early students have been lost to time.

“We did have a major fire in 1856," Lundell said. "Then, of course, the Civil War in the 1860s. So, a lot of our early records were lost."

A law passed in 1901 forced Maryville College to segregate after more than 80 years of acceptance for everyone.

“Maryville College knew that we could not fight that law—we did consult with lawyers to find out if that was possible," she said. "But really, there was no way that we could win. So, we were forced to segregate."

Maryville College remained segregated for more than five decades until Brown vs. Board of Education changed everything.

"As soon as that law was passed, that the federal law that overrode all of the state laws, we were able to desegregate, and to once again, become an integrated institution," Lundell said.

The first Black students to return to Maryville College after desegregation are forever known as the “Maryville Six.”

“They were the first six that came back after in 1954," she said. "One of them graduated. Her name was Nancy Smith, she graduated in 1960. They all went on to become pillars in their local community."

Throughout its legacy spanning more than 200 years, Maryville College has been a beacon for equality and has seen its Black alumni go on to see great success.

“Those include folks who went on to become teachers and ministers, dentists, physicians, attorneys, pharmacists—all sorts of different occupations," Lundell said.

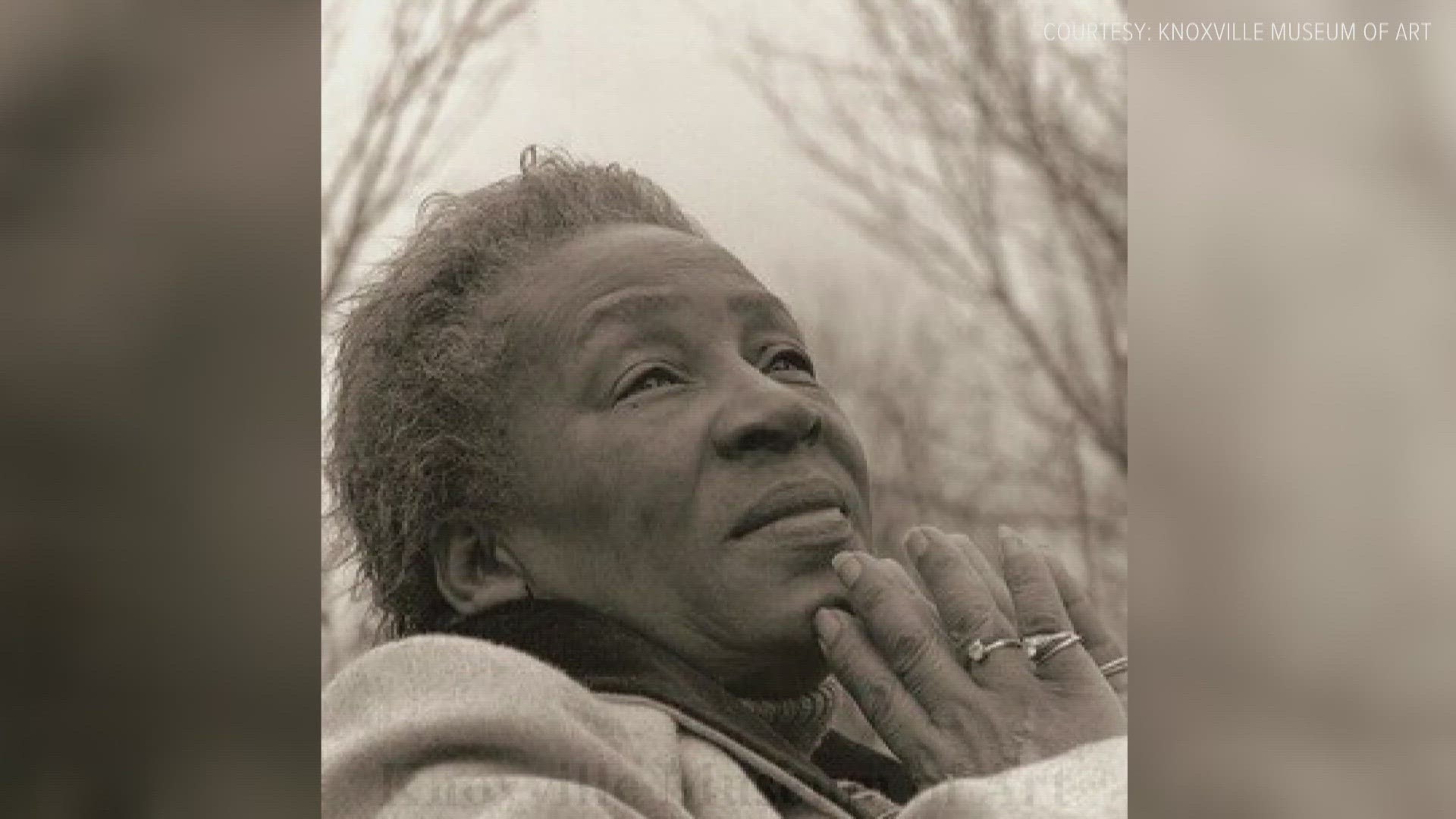

The Unusual Art of Bessie Harvey

In 1929, Bessie Harvey was born the seventh of 13 children in Dallas, Georgia.

Her childhood was tough. Her father died young, which pushed her mother to alcoholism.

“You can imagine what it was like growing up in that situation, then I married when I was 14," Harvey said in an interview with WBIR in 1989.

By 1968, Harvey was divorced and moved to Alcoa with her eleven children. She eventually started working as a nurse at Blount Memorial Hospital. During her time there, she found a muse in nature.

“I would walk along, you know, I would see a piece of wood... it would say something to me, you know, it would be a person or something," she said. "It was shaped to be something that it wasn't. It was a piece of wood, but to me, it might be an animal or person."

Using materials such as beads, glitter, cotton and paint, Bessie was able to express herself in the debris she found.

“I do it for different reasons," Harvey said. "Sometimes when I seem burdened or something, I can pull it out of me into the wood. Then sometimes I just have an urge to do it. It just seems like something bothers me until I go and do this. Like, I might see a piece with my eyes closed and I had to do it. See, I had to get rid of it. If I don't put it out, it won't leave me. I had to get it out of me."

Harvey's unique art style wasn’t understood at first.

“When I began to make these dolls, a lot of people said it was voodoo," she said. "A lot of people were like, they was afraid of them."

But as time went on, people grew to appreciate it.

“So many people have gotten my pieces, then they would tell me how much joy and peace it had brought in their home," Harvey said.

Harvey died in 1994. Her work has been featured in more than 50 exhibits across the country both during her time as an artist and posthumously, including the Knoxville Museum of Art.

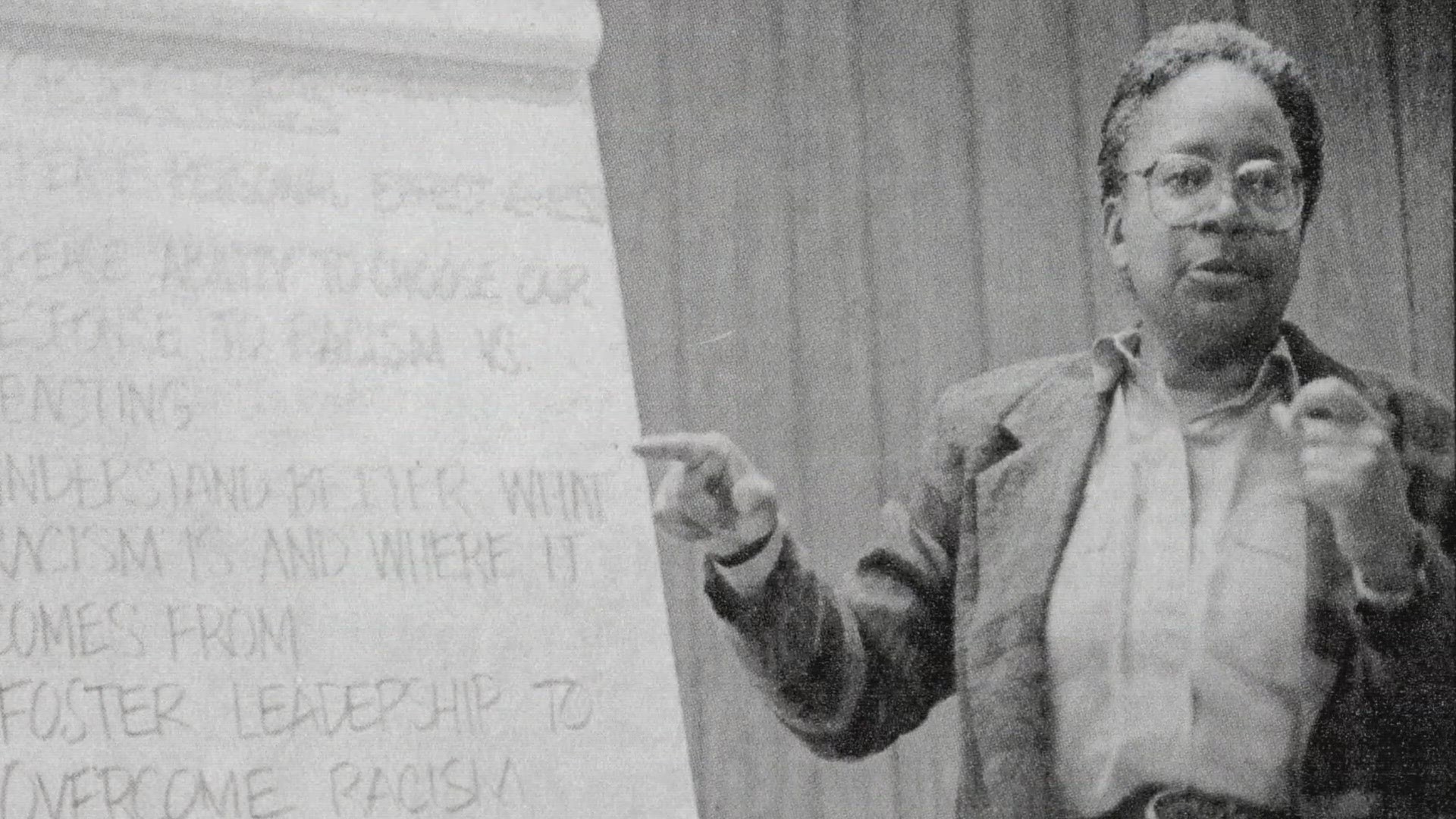

Dorothy Kincaid

Dorothy Mitchell-Kincaid grew up in Alcoa. She spent years of her life fighting for change with multiple organizations including the Highland Center in New Market.

“I think saying Dorothy was a force of nature would be very true," Professor of Black History and former Alcoa resident Andrew Baskin said. "She was a fighter. She inspired me and she inspired other people in the 13 streets to invest in the community and to fight for change."

Later in life, she was forced to fight a new battle.

“In 2012, Dorothy found out that she had pancreatic cancer," Baskin said. "And when she was given the diagnosis, I think that she was only supposed to live a year. Dorothy lived seven. And during those seven years, Dorothy lived as if she was going to live forever."

After her diagnosis, Dorothy took it upon herself to tell the stories of the people from the area she grew up in.

“The focus was upon collecting the oral histories of African Americans of Blount County to tell their story," he said. "Because normally everybody's story is told. The issue is going to be whether it's going to be told by someone else, or if it's going to be told by you."

She also helped found the Beloved Community Outreach Foundation which helps people with cancer make ends meet.

“Dorothy was fighting cancer herself while she was thinking about those who will be fighting cancer,” Baskin said.

Dorothy stressed the importance of voting to the citizens of Alcoa and became a campaign manager for Jackie Hill who was running for the county commission. This campaign led to history being made in Blount County.

“Jackie won. Jackie won a seat on the Blount County Commission, as a Democrat and the first black woman who was elected," he said.

Dorothy died in 2019, but her contributions to the city of Alcoa leave behind a legacy worthy of her being known as “The Conscience Of The 13 Streets.”

“Dorothy was like so many of us, and I guess good southern people," he said. "We had a front porch. You sat on that front porch, and you saw the people and you saw what was going right and what was going wrong, and you decided to do something to make it better."

Alcoa Desegregation

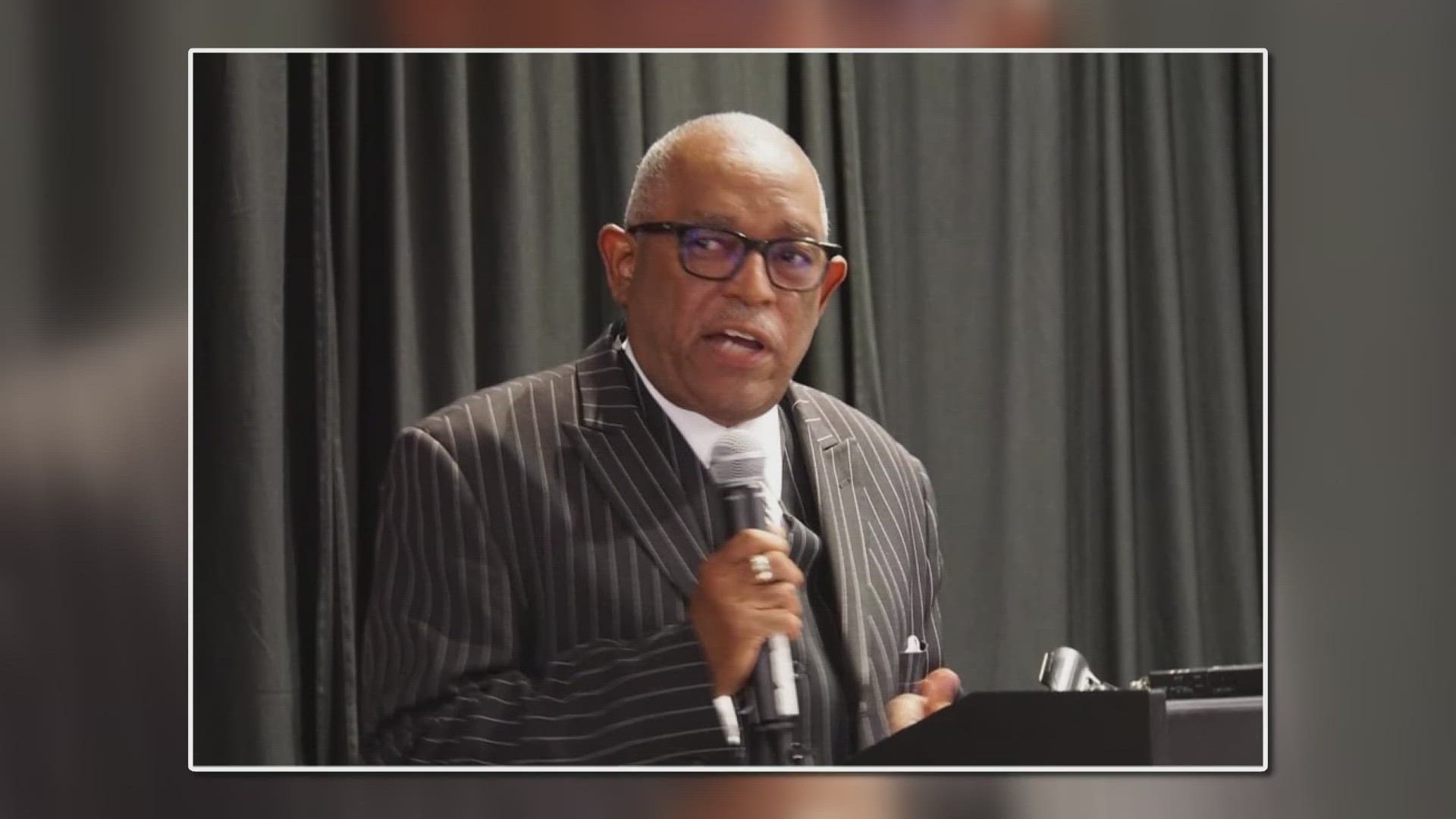

The story of Andrew Baskin's life begins in the same way as many other African Americans living in Blount County during the 1950s and 60s—in the shadow of Alcoa's aluminum smelting plant.

Black workers and their families populated the company town's thirteenth streets, all of which were named after famous scientists.

At the center of that community stood black churches, a cemetery for black plant workers, and an all-Black school—Charles M. Hall.

"My education was spent at Charles M. Hall," he said. "It was two streets over from where I live, because I still I could walk there every day, I could cut across the field and go to school."

While he grew up in Alcoa, the nation surrounding Baskin and his community was rapidly changing.

1964 saw the Civil Rights Act and 1965 saw the Voting Rights Act. But, a landmark Supreme Court decision a decade earlier would have the most impact on a young Baskin.

The Brown vs. Board of Education declared that while segregated schools were separate, they were not equal or constitutional.

Still, students from the thirteenth streets would continue graduating from Charles M. Hall for the next 14 years until the class of 1969.

Unfortunately for Baskin, he would not get to graduate from a school integral to his upbringing.

"We found out that our class was not going to be able to graduate from Charles Hall," Baskin said. "If we stayed in the Alcoa City School system, we were going to have to graduate from Alcoa High School

Across the southern United States, the desegregation and integration of U.S. public schools brought heightened tension and often violence.

While things never got physical at Alcoa, students of Charles M. Hall did not have an easy transition.

"This whole process of desegregation, when we talk about it, too often, I think we look at it as—well, there were no riots, there were no police," Baskin said. "Okay, everything went smoothly. That's not true. I think I would say that the white students and the white teachers did not necessarily want us there. And I would think many of the African Americans would tell you, honestly, now they didn't want to be there."

As high school graduation approached, Baskin knew he only had three options: join his father to perform demanding labor at the aluminum plant, join the military at the height of the Vietnam War or go to college.

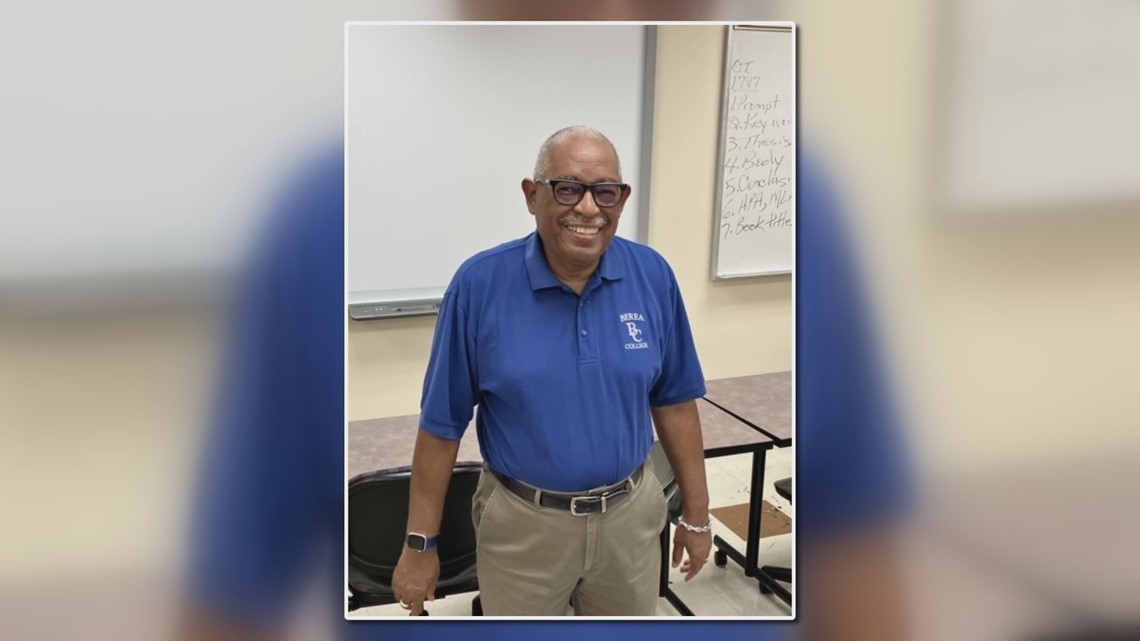

"I remember one line from Forrest Gump, which is one of my favorite movies," he said. "I can't wait. He said 'He can't remember the day he was born.' I can't remember the day I found the catalog from Berea College, but that changed the direction of my life."

Located in the foothills of central Kentucky, Berea College is a highly competitive, tuition-free institution—primarily serving economically disadvantaged students from across Appalachia.

In 1969, Baskin applied to only one school and was accepted—Berea College.

Despite being the first racially integrated college in the South and counting the father of African American History Carter G. Woodson among its alumni, Baskin and other black students still had to fight to be visible at Berea during the early 70s.

"We want to be accepted as equals, we want Black History to be taught, we want to see black teachers, we want to see people like us," Baskin said.

He would make good on that last desire. After graduating from Berea in 1972, Baskin would continue his education, earning a Master's Degree from Virginia Tech.

Baskin then embarked on a nearly five-decade-long career in higher education. Eventually teaching thousands of students.

The man now known as "Professor Baskin" would spend 36 years of his career with the institution that changed his life. He became a distinguished alumni and professor emeritus of African American studies.

"I never thought in 2024 that I would still be living in the town of Bria and have any really close association with Berea College," he said. "So, it's a reminder that I don't think we all never know where life is going to lead us."